Golf trails are nothing new. Courses and clubs have formed marketing partnerships for years with varying degrees of impact.

In the United States alone there are at least 50 trails. Texas has five separate of them. Colorado Golf Trails is one marketing entity, but it promotes 10 different trails within that state, and some of those trails have as many of 12 courses. Go to http://www.golftrips.com/golftrails/ to check out the various trails out there.

Most famous is probably the Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail, which unites 11 Alabama golf facilities. It’s been a rousing commercial success, but some of the “trails’’ amount to nothing more than websites.

I’ve played all the courses on Indiana’s Pete Dye Golf Trail and some courses on a few of the others, including the Robert Trent Jones. This winter, though, I’ve been introduced to one that is different – and in some ways better – than all the others.

The Florida Historic Golf Trail is a collection of about 50 courses. Most were established between 1897 and 1949. All have been publicly accessible for at least 50 years and remain open to the public. Some have been at least partially updated. Some have conditioning issues. Some have retained much of their old-time charm. All would be worth a visit.

One good way to get a feel for an unfamiliar area is to play its golf courses. While I’ve played only five courses on the Florida Historic Golf Tour, four this year, it’s my belief that you can generally get a very affordable golf experience along with a history lesson if you opt for a stop on this list of links.

Florida’s golf history is one of the oldest in the nation, and courses on this trail are spread throughout the state. They’re listed at FloridaHistoricGolfTrail.com, and the site greatly enhances a visit to one of the courses because it provides historic details on each layout and the area surrounding it.

For instance:

Riviera Country Club, in Ormond Beach, started as the cornerstone of a housing development called Rio Vista on the Halifax in 1924. About all that’s left from that development are the elaborate arches that formed the entryway. The Meyers family has owned Riviera since 1953 and it’s the home of the longest-standing mini-tour event in the country, the Riviera Open, which made its debut in 1960.

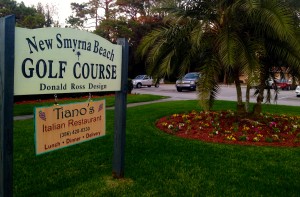

New Smyrna Golf Club in New Smyrna Beach, might be the last 18-hole course designed by legendary architect Donald Ross. Now a municipal course, New Smyrna lists its opening in 1948 — though the Donald Ross Society says it was a year earlier. Only one other Ross designs, Lianerch-McGovern in Haverton, Pa., was listed in 1948 by the Society. Ross died on April 26 of that year.

Ross, who designed over 400 courses world-wide — most notably Pinehurst No. 2 in North Carolina, N.C. — was in the process of completing his last course at Raleigh (N.C.) Country Club at the time of his death.

Other Ross courses are included on the Florida Heritage Golf Trail. Palatka was another that I played. Ross designed it in 1925 and it’s been the home of the Florida Azalea Amateur since 1958.

The Bobby Jones Golf Complex in Sarasota also had a Ross influence, but a relatively minor one. He designed the first 18 of the 45 holes now there. The nines of Ross’ course are now split among the two existing 18-holers and a nine-hole executive course is named in honor of Scottish-born Colonel John Hamilton Gillespie. Gillespie built a two-hole practice course in Sarasota in 1886 and because of it the city has claimed to be “the Cradle of American Golf.’’

While Ross courses are prominent, other famous designers like Seth Raynor and Tom Bendelow have courses on the trail as well.

Another course in the mix is Dubsdread, in Orlando. The late Joe Jemsek liked the name so much he used it for his famed No. 4 course at Cog Hill in Lemont, IL. – for 20 years the site of the PGA Tour’s Western Open. Orlando’s Dubsdread was a PGA Tour site, too. It hosted the Orlando Open from 1945-47 and such legendary players as Patty Berg, Jimmy Demaret, Sam Snead and Babe Zaharias were frequent visitors in the 1940s and 1950s.

A Chicago architect named W.D. Clark designed the Jacksonville Beach Golf Links in 1928. Ten years later Golf Magazine rated it with Pebble Beach, Oakmont and Pine Valley as among the hardest courses in the nation. That course eventually became what is now the Ponte Vedra Inn & Club’s Ocean Course.

All these places have a different feel about them, something you don’t find at the newer facilities.

The Florida Department of State created this golf trail with funds from the National Park Service. The courses on the trail, strangely, haven’t embraced their membership as much as they could. The promotional literature consists simply of a scorecard listing of the courses, with places to record the date and score posted for each round. Those promotional scorecards were hard to find at some of the courses we visited.

One aspect of this ongoing golfing adventure is noteworthy, however. Most of our nearly 20 rounds played this winter were on much newer courses, and there was rarely a delay in play on any of them. That wasn’t the case in our visits to Palatka, Riviera or New Smyrna. Those courses may be old, but they were packed with people having a good time and many of them were staying after their rounds to socialize in the clubhouses. There’s a message there some place.